What is a failure? First of all, a failure is a cost that must be minimized. It needs to be minimized by not using cheap poor-quality parts, poor-quality tools, and other restrictions in the Maintenance Department itself. The reduction of costs due to the prevention of failures is conducted by analyzing them and drawing the right conclusions for the future. We then not only reduce costs, but we can even generate savings. However, in order to follow this path, data is needed – historical data from failures in the form of Maintenance reports.

Therefore, I will refer here to a survey that I have recently conducted. The results are a bit surprising. As many as 34% of respondents work in companies where post-failure reports are not carried out, and thus the chances of improvements and the reduction of downtime costs are very limited.

However, following its definition, failure is a sudden and unplanned stoppage of a machine, or the loss of its functionality. The loss of its functionality is understood as an inability to continue further production while maintaining the required parameters (e.g. dimensions, efficiency, quality, etc.).

Failures in a production company are natural. It is “acceptable” that a machine has a fault, which is followed by an unplanned downtime. On the other hand, downtimes, which clearly affect the performance and inhibit, or even prevent, the implementation of the production plan, are “unacceptable”. In the worst-case scenario, they affect the timeliness of shipments to customers.

However, in order for it not to be the case that each, or most, of the reasons for failures to implement the production plan are caused by the poor condition of the machinery park, appropriate KPIs are used in Maintenance Departments. They are meant to inform us whether the failures we deal with on a daily basis are on an “acceptable” level. However, there is still a report between an indicator and the failure. The failure report.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is the failure report?

A correctly prepared failure report is a very important document in the Maintenance Department (MD). It provides a lot of information about failures, which can become an impulse for Continuous Improvement. In MD cells, the work of which is supported by information systems such as CMMS (software for managing the MD), reports are generated automatically. This facilitates work and helps in the analysis of data for the future.

Failure reports should be tailored to the needs of the organization. Too little information will mean that they are only a trace of the defect, from which it will be difficult to extract data and perform a reliable analysis of the failure. Too much information will result in information noise. What then should a “standard” failure report contain? Certain data like the machine’s number, the line, and the date are basic, and I believe I don’t have to write about them.

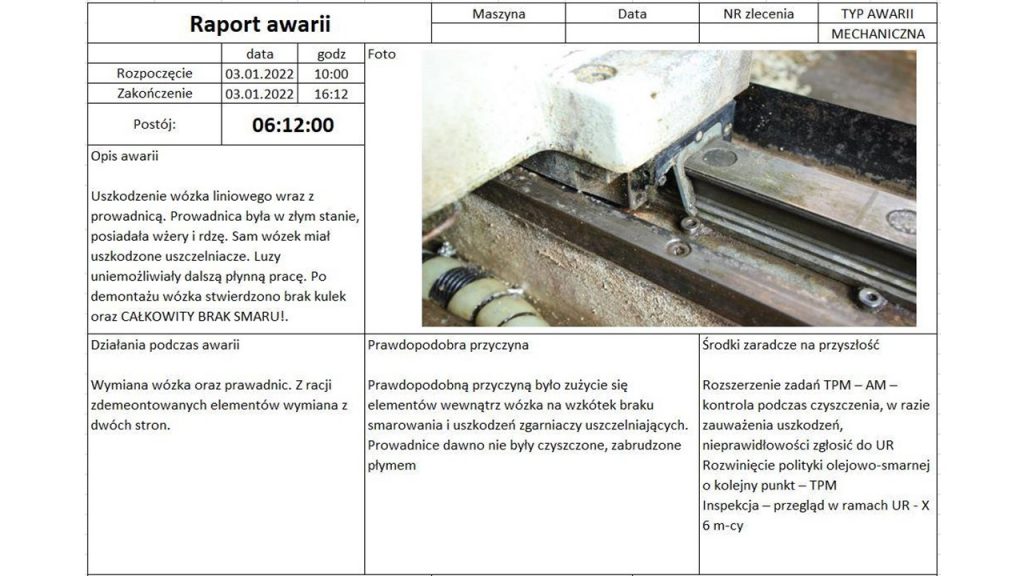

Fig. 1. Breakdown report – polish version (example)

TIME IS MONEY

One of the basic data is the hour of reporting the defect to the Technical Department. This data can tell us about the time the Production Department (along with support departments) spent on the self-removal of the defect. After several unsuccessful attempts, a failure is reported. The time from the machine stopping to reporting it to the MD may in some cases be counted in hours! This has a huge potential for improvement. Establishing clear and simple rules for escalating the problem to the Technical Department will reduce machine downtime and improve productivity for the plant.

The next data, after the hour of reporting, is the time of the technician’s arrival at the site of the failure. Here, there is also the potential for performance improvements. By working on the reduction of this time, we influence the reduction of MTTR, i.e. the duration of the failure is shorter. The long waiting time for support may indicate, among others, the long distance that a technician has to cover between the MD workshop and the place of the failure, or may suggest insufficient resources in the MD’s structures (machines are waiting for the end of the previous failure). There is room for improvement in both cases.

END TIME

As simple as it may seem, there are different approaches to determining when the failure ends. This results from the interpretation and the approach of what the failure really is. Some people count the time of ending the failure as the hour the technician finishes work and “hands over” the machine to production. Others count the time of failure until the resumption of the production process, while also taking into account the time of setting up by technologists, calibrations, and other necessary tasks that must be performed after the failure – not necessarily by the Maintenance Department. Each approach has its pros and cons. Which one you choose largely depends on how you monitor your production process and its anomalies. The most important thing here is your approach to what you will do with this data.

TYPE OF FAILURE

The division of failures into the categories of hydraulics, pneumatics, electrics and mechanics will allow for the selection of the course of action for the people dealing with Preventive Maintenance during larger analyzes. By knowing what kind of failure is dominant, we can take appropriate countermeasures. Such knowledge will allow, for example, the direction of appropriate training to be planed, or cooperation with companies that are specialists in a given field to be established.

THE DESCRIPTION OF FAILURE

This is an incredibly important part of the report. It’s like a coroner’s report from a crime scene. The person preparing the report should be the same person (or team) that removes the failure. The more details the better. This will be especially useful when we want to come back to certain failures in a few months’ time. Below is an example of two descriptions.

One is vague and doesn’t tell us much.

Linear bearing failure. Wear has occurred. Replace with a new one that has a guide rail.

The second is maybe exaggerated, but it provides a lot of information, and thus gives opportunities to counteract.

Damage to the linear trolley with the guide rail. The guide rail was in poor condition with pitting and rust. The trolley itself had damaged sealants. Loosenings prevented further smooth operation. After disassembling the trolley, it was found that there was a lack of balls and a TOTAL LACK OF GREASE!

As you can see in the above examples, the description itself matters and will ALWAYS influence the quality of the activities of analysts and prevention workers.

ONE PHOTO SPEAKS MORE THAN A THOUSAND WORDS

For me personally, the obligatory element of each report is a photo from the scene.

The first one should be taken when the technician arrives at the machine. The photo should show as much as possible the moment when the machine stopped and the failure occurred. Therefore, in justified cases, it is important to leave the machine in the state in which the operator found the defect. No cleaning, no removal of elements, no removal of components. Contrary to what we may think, this does not help and often makes it difficult to find the cause.

Logo CLP

UNDERTAKEN ACTIONS

Particularly important is the description in the case of complex failures, where we look for the cause by eliminating further potential causes. At the end of such failures, it is not uncommon for “half the machine” to have been replaced while removing the defect, with the causes not actually being so complicated. The icing on the cake is the fact that there will almost always be someone else (e.g. from another brigade, an operator) who already remembers such a failure, its symptoms, and what they then did or replaced for the machine to start. Well, everyone knew, except the guy who removed the breakdown.

Another important aspect of the description of activities is the fact that in the absence of ideas for the removal of disabilities, it serves as a kind of base of knowledge and good practices. Such a Lesson Leaned for the Maintenance Department.

POSSIBLE CAUSE

This part is an introduction to prevention. This is the opinion of the person who removed the failure about why it happened at all. Perhaps the reason was poorly routed signal cables, which were worn and led to a short circuit, or perhaps the reason was a lack of lubrication, or errors of operators… This information may direct other people to take appropriate steps in order to protect the organization against such failures in the future. If it is justified, it is worth enriching this point with the aforementioned photo from the scene of the incident.

FUTURE REMEDIES / COUNTERACTING

The last piece of the puzzle in the report is counteraction. Once again, this is the opinion, very often accurate, of people who remove the failure. Being on the front line when removing failures means that it automatically comes to your mind to counteract them. Adding activities to TPM activity lists, different cable routing, lubrication, or more frequent replacement have a real impact on MTTR, MTBF or OEE.

In the mentioned case, the suggestions for counteracting could be as follows:

- Extension of the tasks of TPM – AM – inspection during cleaning; in case of noticing any damage, report any irregularities to the Maintenance Department

- Updating the oil and lubrication policy with another point – TPM

- Inspection – inspection under the Maintenance Department – X 6 months

The topic of failure reports is broad and I certainly did not cover everything in this article. Finally, I will add one more advantage of creating full descriptions and taking photos of reports after MD activities. Time. I know from experience how difficult it is to analyze failures that occurred weeks ago. Find the people who removed it, phone calls, e-mails, meetings at the machine. And it’s all time. Those who analyze failures, those who repair machines, and those who produce on them.

Tip / advice.

If at the beginning you and your team are scared of creating reports for ALL failures, you can start from those that meet one or two of the following conditions:

- For failures over XX time

- Only for critical machines – resulting from the ABC analysis

I was lucky that everything I learned about Lean, Kaizen, or production optimization started in a Japanese company. There, under the supervision of Japanese staff and during training in Japan, I learned how to approach the Continuous Improvement process. Over time, I also learned about other practices in other companies.