False assumption? Play a Game you can Win!

Planning is an unnatural process. It is much more fun to do something. The nicest thing about not planning is that failure comes as a complete surprise rather than being preceded by a period of worry and depression.

~Sir John Harvey-Jones 1924-2008 – British business leader

Table of Contents

ToggleIs your approach to operational planning unintentionally setting you up for failure?

The causes of delays, excessive firefighting and late deliveries are many and varied. On the surface, they are often put down to poor management of the operational areas themselves. However, the problem can often be found much earlier in the ‘order–to–delivery’ cycle – operational plans based on flawed assumptions about what is possible. If – as often suggested by teams executing those plans – they are unrealistic and not achievable, we can do as much work as we like on improving our operational processes and still not deliver customer orders on time to the required standard.

Put simply, if our plans are overstressing our “production system” by giving it more work than it has the capacity and/or capability to do, then we are planning for failure. Not only that, but we are generating a significant amount of “cost of failure” for all the work we do:

- Expediting “urgent” orders as we fall progressively more behind schedule.

- Rescheduling work to cope with late deliveries of components or information from suppliers or other parts of the business.

- Work is rushed due to time pressure, leading to quality issues and rework that can further erode capacity.

- Different functions, e.g. procurement, production and logistics, will do their best, yet may decide on priorities that do not reflect those of the business or customers and may be different between functions, leading to mis—matches between what materials are available and what is planned to be made.

- There is an increase in work–in–progress because of all the above, tying up both valuable storage space and, perhaps more importantly, cash. The latter may, in turn, lead to liquidity issues.

- Overtime becomes routine, which may be OK for a while, yet progressively leads to a deterioration in productivity as the effects take their toll.

- Colleagues at every level become increasingly overstressed, leading to poorer performance and decision making, increased sickness and absence levels and eventually some leaving the business. These lead to increased labour costs, both to cover absence and to replace those who leave (I was surprised to learn recently that the cost of replacing someone is roughly one year’s salary, irrespective of their grade).

The net result of all of the above is typically a significant reduction in margin. More often than not, overall output falls and certainly doesn’t deliver the increase in profits that may have been hoped for when setting the plans.

Flawed assumption?

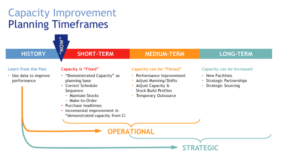

So what is it that leads to unrealistic plans? Over the years, I’ve come to identify a small number of what I term “false beliefs” or flawed assumptions around planning of operational capacity. These are perhaps most obvious in the production of tangible assets – e.g. cars, radios, food and drink – and yet are equally true of “Information based” tasks carried out in an office – e.g. invoice processing – or people–related activities such as hospital care.

False assumption 1: We can do more if everyone just works a bit harder!

The first false belief is that output can be increased if everyone works just a little bit harder. And, of course, there’s evidence that this is true. “Special orders” can be squeezed in and rushed through. While this reinforces the belief, what’s less obvious is the level of “exceptional effort” required to achieve this and the disruption caused to the rest of the work in progress. In turn, this is likely to lead to a drop in overall performance, more special efforts and the start of a downward spiral.

Pic.1

This leads me to planning rule number 1.

Only plan on the basis of what you have demonstrated you can achieve routinely

This rule applies both to capacity (how much we can do) and lead time (how long it takes to do it). What can be done consistently without exceptional effort. On this basis, we can plan with confidence that, barring an exceptional problem, orders can be satisfied on time with the minimal amount of effort. This places the business into its “peak performance zone”, where it is delivering the highest level of value adding work and, most likely, greatest profitability. Beyond this point, either the level of effort required to deliver the additional output becomes excessive and more disruptive to routine or equipment and people are overloaded to the point where performance deteriorates over time (machines suffer from lack of maintenance, people suffer from lack of rest and self care).

False assumption 2: But surely a little “stretch” is good?

One challenge that often comes back to me when I make this point to clients is that it seems counter to the idea of continuous improvement. Surely, they say, we should be challenging everyone to do better and get closer to delivering the theoretical capacity. Of course, in one sense they are right. In the world of Operational Excellence, we are always challenging ourselves to get better; to identify and eliminate “waste” in our processes to improve flow and eliminate non–value–adding activities. So, a level of “stretch” is definitely desirable to maintain focus on improvement. Alternatively, they’ll express concerns that actual output will continue to fall below the planned level, thus reducing the demonstrated capacity, leading to a downward spiral. So, they think, some stretch is needed even to maintain current performance. Again, I’d agree with them. The “false belief” is that this stretch should be included in plans before it is achieved in practice, that somehow a little challenge and tension will keep everyone working at their best. This is all very well when improvement activity proceeds at a pace that keeps up with the “stretch”. The problem comes when the improvement is not realised or takes longer than expected, taking us back into excessive effort, disruption and chaos. Far better, in my experience, to plan on what has already been achieved in practice and only build in higher levels of performance once it has been demonstrated. This leads me to planning rule number 2.

Plan separately for routine performance and improvement

Put simply, short–term plans are based on historical demonstrated performance (capacity and lead–time) to create an environment of predictability and stability so that the business can perform well with relative ease. Separately, set stretching performance goals to improve performance (bearing in mind to connect all of these to overall delivery to the customer and not local optimums as discussed in our previous article). Only once the improvement has been demonstrably achieved and can be delivered consistently should it be incorporated into routine planning.

Following on from this is planning rule number 3.

Once today’s work is finished, STOP!

This is perhaps one of the most challenging rules to put into practice as it works against many of our “natural” instincts. An almost inevitable consequence of applying rule number 3 is that, as improvements are made and before those are “baked in” to the forward plan, work in the improved area will get completed more quickly or output will be higher than required. In these circumstances it can be very tempting to “work ahead” and start tomorrow’s work – “just in case” we have a problem and get behind. Tempting as this is, the most likely outcome is that things will get more chaotic. Upstream areas may not have improved as much yet and may start to feel overloaded and stressed as they try to keep up. Downstream orders may feel the pressure as there is more work waiting. Instead, consider how the time freed up can be used to work on other problems or to develop the people in the team. Perhaps even offer support to allow other teams to work on their improvements so that the overall performance of the business is raised to a new “demonstrated” level.

False assumption 3: We have a standard lead time, no matter what!

Organizations love to quote a standard lead time to customers and, in many regards, that is a great thing. However, it’s important to understand the conditions required for that to be achievable. Firstly, we need to be quoting a lead–time that can be consistently and routinely achieved, not an average, our “best day” or what can be achieved by exceptional effort. Secondly, overall demand must require no more than the demonstrated capacity, otherwise a “queue” of orders will build up somewhere in the system. This will add “waiting time” to the normal lead–time which, left unchecked, will increase exponentially.

This leads to planning rule number 4.

Build into the planning and execution system an indication of when capacity is close to or at maximum

When this indication is given, there are two courses of action:

- Make plans to increase capacity to meet the increased demand.

- Feed the information through to the sales/order intake system to ensure that appropriate lead times are quoted and no unrealistic promises are made.

These are not mutually exclusive and it may take some time to increase capacity, so the response plans should take both options into account.

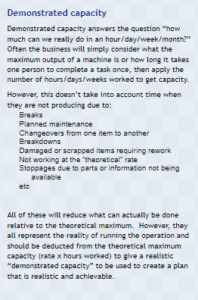

Demonstrated capacity can (and should) be improved

Having said all of the above it is, of course, possible to improve the demonstrated capacity. However, just like routine operational activity, this too has a lead–time and must have a realistic, achievable plan that respects the capacity and capability of the organisation to make the necessary improvements. As the illustration shows, there are a number of “lead–time” horizons to consider.

Pic.2

Short term – Capacity is essentially “fixed”: Incremental improvements in demonstrated capacity can be achieved through local continuous improvement actions and baked into the demonstrated capacity once proven.

Medium–term – Capacity can be flexed: It may be possible to increase capacity by adjusting working hours, adding additional labour or temporarily outsourcing manufacture. These changes will have a lead–time associated with them, for example to negotiate new working agreements or hire additional staff.

Long–term – Capacity can be increased: Significant increases in capacity are likely to require a more significant investment and take longer to achieve. These can include such things as buying new equipment, building new facilities and developing strategic partnerships.

A great plan is only the start!

If the above planning rules are followed, there is a far higher probability that those plans can be executed routinely and without excessive effort required to keep things on track.

No plan survives contact with the enemy

~Helmuth von Moltke 1800–91 – Prussian military commander

Naturally, not everything will always go to plan and there will still be the occasional issue to be resolved. However, with this firm foundation there will be more time to address those issues in a timely manner. Having said all of the above, a great plan is only the beginning and success is not guaranteed. Without an equally great “execution system” to ensure those plans are well–delivered the anticipated benefits will not be achieved. This will be the theme we’ll come back to in next month’s article.

So, are you playing a game you can win?

The plans of the diligent lead surely to abundance, but everyone who is hasty comes only to poverty.

The Bible – Proverbs 21:5 (English Standard Version)

I wonder which “false beliefs” or inappropriate “planning rules” you have identified as you have read the above? Perhaps you already know? Or maybe you need to dig a little deeper to find out? In either case, our Operational Planning Diagnostic Workshop may be a great next step to flush out the “bugs” in your planning process. Built on over 30 years’ experience of improving cross–functional business processes, the two–day workshop is a proven way to identify the flawed assumptions and ‘gaps’ in your operational planning process and define the actions required for a more robust operational planning process. Facilitated on your premises or at another venue convenient to you and tailored to the specific requirements of your organization, the workshop will enable your teams to explore their current planning process, come to a well–defined vision for a future process based on a clearer understanding of the assumptions and create a plan for implementing the future process. The outcome will be a clear vision for a revised planning process to deliver operational plans that are accepted by everyone involved as realistic and achievable. With that in place, operational teams will have a firm foundation on which to refine their execution processes to ensure that products and services are delivered to your customers on time, every time without overstressing your teams. Whether you’re ready to book or workshop or simply want to find out a bit more, we’d love to talk to you.

Harvey Leach is passionate about helping organizations acquire the knowledge, skill, and culture they need to achieve Operational Excellence. Following a successful career in the automotive industry with Rover and BMW Group, where he worked in a variety of roles covering R&D, production and corporate strategy, Harvey has worked as a consultant, trainer, and coach since 2004. He delights in seeing teams “come alive” as they discover how they can apply the same principles that underpin some of the world’s leading companies to their organization to achieve impressive improvements in performance and more fulfilling lives.