TPM means zero breakdowns, zero losses, zero errors, and high

OEE. This is the dream of every production manager and every maintenance service. Why then, in so many companies does TPM simply die after the initial enthusiasm? The article describes an interesting history of a certain

TPM implementation. The problems encountered by the people implementing this program are presented. The causes of these problems are identified and practical solutions that can inspire any company implementing TPM are provided.

What is TPM?

The TPM system (Total Productive Maintenance) is a set of techniques developed in Toyota plants, which allow for the maintenance of a stable, reliable machine park. The TPM system involves the maintenance of machines and devices, which is carried out inside the company by operators and maintenance staff. Thanks to the appropriate organization of the cooperation between the MD (Maintenance Department) and the Production Department, it even enables a heavily depleted machine park to be kept in operation, and significantly reduces any threats to the continuity of production, such as failures or unplanned downtime. Zero breakdowns, zero losses, zero errors, high OEE – this is the dream of every production manager and every maintenance service. Why then, in so many companies does TPM simply die after the initial enthusiasm?

A story of a certain implementation of TPM

I am a production manager. Half a year ago, we decided to implement TPM in our company. We started with some workshops, during which we thoroughly cleaned several machines, and found and marked dozens of faults on each of them. We managed to remove many defects relatively quickly. The fixing of others stretched out over time, but we finally dealt with them. The workshops worked very well for improving communication between the Production and MD, and we probably learned a lot from each other thanks to the fact that we got to know each other’s job positions and priorities. There was an increase in awareness and commitment in both teams. The next step was to define the scope of the autonomous maintenance activities for operators. We chose the activities, agreed that we would devote 20 minutes to them, and then developed instructions. This time was available earlier, but no one knew what was meant to be done and who was meant to do it during these 20 minutes.

Beginning of TPM Journey

We started the program. Unfortunately, problems started to appear almost immediately. Foremen reported to me that autonomous maintenance was more time-consuming than the agreed 20 min. They sometimes used it as a reason for less job being done on a machine. In turn, the Maintenance Department complained that operators resigned from performing some randomly chosen activities. They do this due to their own convenience and explain “that they are not able to do all of it anyway”. Other employees, because of being in a rush, performed the agreed cleaning and maintenance, but only roughly.

We had to somehow react to these problems, especially as the management was pushing hard for the TPM implementation to be successful. After a difficult and stormy discussion, we decided to reduce the scope of autonomous conservation. There were voices from the MD that “all this TPM ceases to make sense” after such a reduction. On the other hand, foremen argued that “they waste 20 minutes every shift to do MD jobs, and that they will never get it back for production”. They did not realize at all that thanks to this they would have less breakdowns and smoother work (“after all, failures are a matter for the MD”).

At the moment, the TPM issue has stalled and, after a phase of initial enthusiasm, become a major problem in the relationship between the MD and Production.

Main problems in TPM implementation

Many people will probably be able to refer this story to their situation. This is a typical development of accidents, which affect dozens of manufacturing companies facing the difficult task of implementing the TPM system. Why did this story turn out this way?

Problem No. 1 – Conflict between Maintenance and Production

A conflict of interest between the Maintenance Department and the Production Department.

Description of the problem

In every manufacturing company, each department has its key performance indicators (KPIs), for which it is assessed by the top management. In the case of the MD, these are usually indicators such as MTBF (mean time between failures) and MTTR (mean time needed to repair a failure). In turn, the Production Department is usually assessed, among others, by its efficiency, productivity and quality. Of course, there can be many more KPIs for each department. However, there is a rule: they are different for different departments. In most cases, the implementation of the TPM system starts with the involvement of operators in cleaning activities on machines, followed by maintenance activities. This is called autonomous maintenance. Unfortunately, this commitment requires the above-mentioned 20 minutes for each production shift in order for them to perform autonomous maintenance activities at a time when the machine needs to be shut down. At this point, a conflict of interest arises, as production workers who are assigned (by costs) to the Production Department perform tasks that improve the KPIs of the MD. At the same time, the KPIs of the Production Department decrease because in the aforementioned designated 20 minutes the production on the machine is stopped and, consequently, the number of manufactured products per shift decreases.

Reason No. 1

KPIs are assigned to individual departments, and not to a specific production line or area of production.

Solution

A way to eliminate this cause of the problem may be to appoint a value stream manager in the company, who is responsible for the efficiency of a given production line or a given production area. In this solution, we suggest abandoning the traditional division into the following departments: MD and Production. Instead, we recommend that you designate a specific number of value streams in the factory and then designate managers and unified KPIs for those streams. Each value stream has the same KPIs. The value stream manager should therefore be equally assessed with regard to the failure rate of machines and the number of manufactured products. A value stream manager would have some mechanics, foremen, leaders and operators assigned to the production areas in a given value stream. In front of the top management, the value stream manager should be assessed for the efficiency of the production line or the production area, and therefore the availability and use of machines, as well as the quality of products. Depending on the specificity of the company, the value stream manager may take care of, for example, two production lines or three production areas.

Reason No. 2

Looking at the results of KPIs in the enterprise in the short term.

Solution

The solutions presented above for reason No.1 (appointment of the value stream manager) indirectly also affect the elimination of this cause. It is in the interest of the value stream manager to look at the results in the long term. If such a manager is assessed for the efficiency of the use of a production line or production area, he is interested in reducing the failure time, even at the cost of short-term losses in efficiency. A conscious value stream manager knows that the investment in spending time on autonomous maintenance will certainly translate into fewer failures in the future, and therefore greater efficiency. All Production Managers in the traditional production structure are certainly aware of this fact, but they also know very well that autonomous maintenance activities will first improve the KPIs of the MD.

Problem No. 2 – Autonomous Maintenance in TPM

Autonomous maintenance activities performed by operators are too time-consuming.

Description of the problem

Before specific activities to be performed as part of

autonomous machine inspections are assigned to operators, and before they are required to carry them out properly, several arrangements and actions must be made. First, the scope of activities and the standard of their performance should be defined. In a nutshell, a

manual or SOP that includes the best-known and correct way to clean, check, lubricate and tighten key components for a machine should be developed. The next step is the training of operators, which is supported by the auditing process.

The SOP of maintenance activities, as mentioned before, is supported by visual instructions that allow operators to learn to perform operations properly and in less time, whereas in the case of supervisors, it enables them to effectively audit the autonomous maintenance process. The problem is that, despite the correct implementation of autonomous maintenance, it quickly turns out that the agreed activities take more time for operators than is allocated for them (for example, 15 or 20 minutes per shift). This in turn causes the operators to “solve” the problem by themselves: they do not perform all the agreed activities and often reject the most uncomfortable or unimportant ones, or they perform all the activities incorrectly due to being in a rush.

Reason No. 1

There are too many activities, and they do not have assigned priorities and the required frequency of execution.

Solution

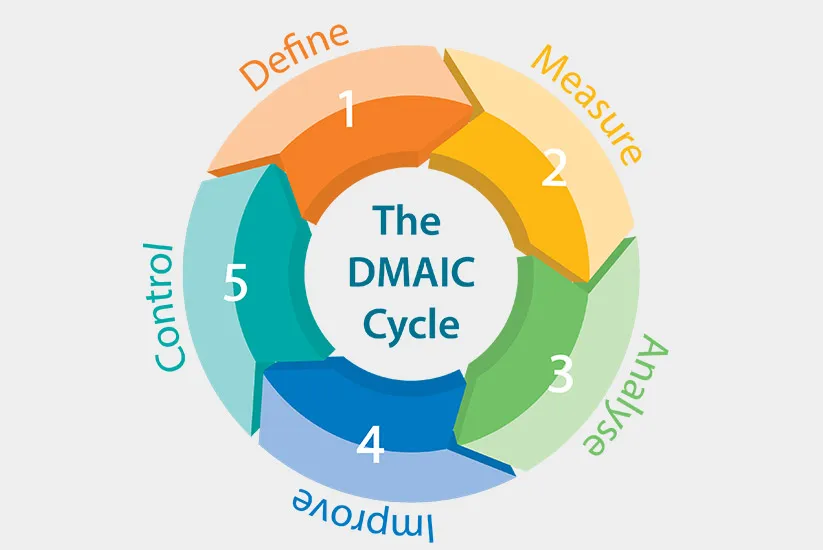

It is a natural inclination to include, “just in case”, as many points as possible in autonomous maintenance. Time constraints, however, obviously mean that the set of activities should be carefully thought out. The activities for autonomous maintenance should be selected while taking into account which of them are the most important and which of them have the highest priority. Afterward, for each activity, the optimal frequency of its execution is determined, which should be marked on the instruction. Should we do the least important ones at all? Certainly, but maybe it will be enough if e.g. I tighten a screw once a day instead of once per shift? It is also important to choose activities with regard to the history of the failure (“what to check so that this failure does not happen again”), and not the aesthetics of the machine (“so that the machine is clean”).

Reason No. 2

At the time of determining the set of activities for autonomous maintenance, we do not know the real time of their execution. We decide what should be done based on estimates, and not reliable empirical data.

Solution

Once the standard for cleaning, checking, lubricating and tightening operations is established, they need to be practiced “live”, and the previous estimate must be verified with actual measurements that are made using a stopwatch. In turn, collecting empirical data will allow us to make the right decision in a given case, i.e. which activities should be included in the autonomous maintenance. Moreover, this will facilitate the planning of maintenance activities and their standardization in the future.

Reason No.3

The activities involve a lot of waste (e.g. walking). Nobody has ever analyzed how much time in these activities they spend effectively (Value adding – VA) and how much time they waste (Non-Value Adding – NVA). There was no process of improvement and the elimination of waste (e.g. using the 5W1H method). Lean cells that are responsible in companies for the process of eliminating waste are usually personally assigned to the Production Department, not to the MD. As a result, Lean cells are often not interested in improving maintenance activities. This is because there are anyway 20 minutes allocated for them (the Production Department will never regain them back for production processes). MDs, on the other hand, have neither the experience nor the competence to conduct such an improvement process.

Solution

Activities performed within AM should be subjected to a normal improvement process – like any other production or logistics work. Typically 60-80% of the time spent on autonomous maintenance is wasted (walking around the machine to get to the other side, bending underneath it, going upstairs to check something, unscrewing covers, etc.). Simply drawing a spaghetti diagram can tell us this. The improvement of autonomous maintenance activities should simply look the same as the improvement of activities performed at the workplace through analysis, changing the sequence of activities, or changing the layout or arrangement of tools. It also opens up a huge field for the creativity of operators and the improvement of ideas.

Summary

Our many years of practical experience show that the

TPM system is a “soft” tool, i.e. it depends on a human factor and human communication. If someone meets the definition of the TPM system for the first time, they will certainly think about mechanics or operators working to improve the efficiency of using a machine. Yes, this is a very important element of TPM. Nevertheless, the most important thing when starting the implementation of the TPM system is the building of good communication and the making of reasonable divisions regarding responsibilities at the early stage of implementation. Problems appearing between the Production Department and the Maintenance Department are often a result of systemic reasons, such as the method of evaluating both the achievement of goals and the responsibility for indicators. In turn, in many companies, improving the maintenance of a machine is a “no man’s land”, for which no one feels responsible. Considering these topics at the beginning of the implementation will allow for a significant extension of the life of the TPM system in any company, and thus enable the company to get closer to the goal of zero losses, zero failures, and zero defects.

Research Project Coordinator at Lean Enterprise Institute Poland